I began my observance of Tisha B’Av early this year.

Tisha B’Av, the 9th of Av, is a day when we mourn the Temple’s destruction and other calamities befallen our people. We attune to the brokenness in our world, our lives, our bodies. It is the beginning of teshuvah, the process of turning and returning that we seek to complete at the spiritual height of Yom Kippur.

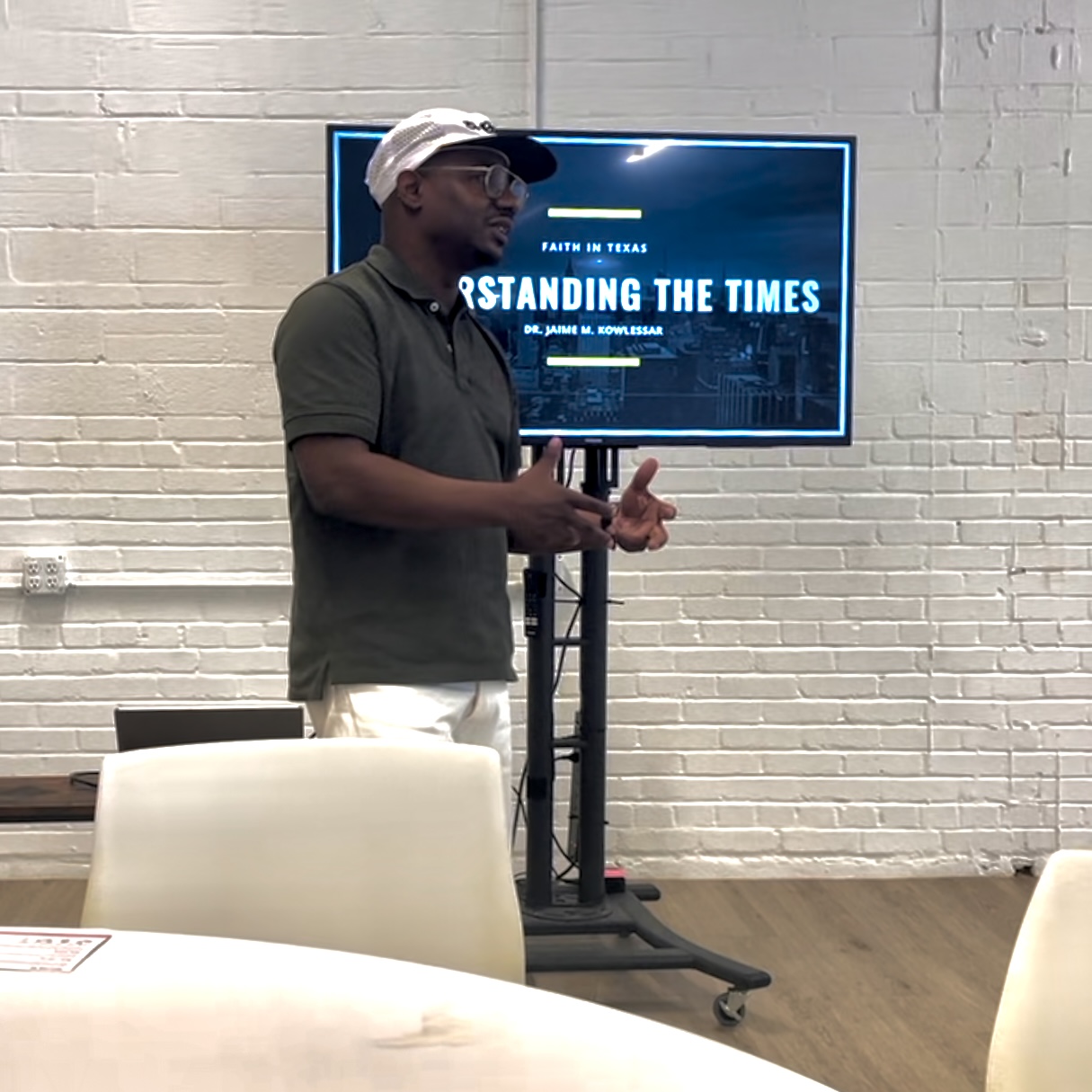

Yesterday, twenty clergy from diverse backgrounds gathered at City Temple Seventh Day Adventist Church in South Dallas. We were joined together through our involvement with Faith in Texas, a multi-faith, multiracial organization committed to racial and economic justice. After detailed instructions and a moment of prayer, we climbed into the thirty passenger bus and drove to Venus, Texas.

We passed through open farm country until suddenly I spotted on the horizon a sprawling facility that looked like a large warehouse. We had arrived at the minimum security Sanders Estes Prison. This unit has around 1000 inmates and is operated by a private company called Management and Training Corporation. MTC operates prisons for the state of Texas as well as a dozens of other facilities across the country, all with the mission to prepare inmates for successful re-entry through a host of programs.

I began my observance of Tisha B’Av in Venus, Texas, miles and worlds away from the service that will take place here tomorrow evening. And yet, the experiences are in fact joined by our sacred duty to face the brokenness that exists both within and around us. And by brokenness I mean that our country fails to uphold its moral responsibility when a massive amount of resources go to sending poor people to jail instead of resources invested back into the community, into schools and drug rehab programs. This is best illustrated through the following story in the book The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander:

Imagine you are Emma Faye Stewart, a thirty-year-old, single African-American mother of two who was arrested as part of a drug sweep in Hearne, Texas. All but one of those people arrested were African-American. You are innocent. After a week in jail, you have no one to care for your two small children and are eager to get home. Your court-appointed attorney urges you to plead guilty to a drug distribution charge, saying the prosecutor has offered probation. You refuse, steadfastly proclaiming your innocence. Finally, after almost a month in jail, you decide to plead guilty so you can return home to your children. Unwilling to risk a trial and years of imprisonment, you are sentenced to ten years’ probation and ordered to pay $1,000 in fines, as well as court and probation costs. You are also now branded a drug felon. You are no longer eligible for food stamps; you may be discriminated against in employment; you cannot vote for at least twelve years; and you are about to be evicted from public housing. Once homeless, your children will be taken away from you and put in foster care. A judge eventually dismisses all cases against the defendants who did not plead guilty. At trial, the judge finds that the entire sweep was based on the testimony of a single informant who lied to the prosecution. You, however, are still a drug felon, homeless, and desperate to regain custody of your children.

I began my observance of Tisha B’Av in Venus, Texas.

Granted, this was a four star unit, as far as prisons go. They have a Prison Entrepreneurship Program which challenges participants to be better partners, fathers and community members. Several inmates have gone on to start their own businesses. There is the P.A.W.S of Hope program which rescues dogs from shelters, trains them and then connects the dogs to families who adopt loving, happy furry companions. As I witnessed, the inmates open up to their canine friends and take great pride in their work.

And yet, despite these amazing rehabilitation programs, it is still a prison. There were no windows looking out on trees. All the inmates wore the same white uniform with facial hair, tattoos and skin color the external indicators of individuality. And though fellow inmates can become a kind of family, the majority of men have partners, children, parents and friends who feel their absence with each passing day, and vice versa.

From a Jewish perspective, according to our traditional texts, restitution, rather than punishment, is the goal. Incarceration–this is what the “other nations” do, for example, when Joseph was held in an Egyptian jail. The limitation of an individual’s mobility and ability is seen as a potential hindrance to the work of teshuva. Plus, we are instructed to see a person who has done the work of rehabilitation as entering his or her life with restored wholeness. Checking a box when seeking housing or a job is a continued reminder of a past offense, pegging a person as tainted, and not inherently filled with future potential.

Now I want to be clear, our sources state we need to follow the law of the land in which we reside. Breaking the law must have consequences and some of the men are deeply troubled and misguided. Perhaps for some, no amount of rehabilitation could change their ways.

However, many inmates are determined to turn their lives around. I met one young man pursuing his GED. Growing up with dyslexia, he never experienced the support needed to help him succeed. Starting in seventh grade he would just walk by his school in the mornings. Nobody cared, nobody noticed. Until now. A retired DISD teacher with a warm and calm demeanor is working with his learning challenges and cheering him on. Why must it take entering prison for a bright young man to find the resources and concern necessary for him to succeed? Here right before me was living evidence of the phenomena we call the school to prison pipeline, one main cause of mass incarceration in our country.

If you are interested in exploring how we can continue to affect change in keeping with our Jewish values on a range of issues and learn more about our civic engagement campaign please make note of the save the date in your Shabbat handout. Just Congregations + Advocacy Committee present a “Summer House Meeting” on Aug. 8th at 6pm in Pollman Hall with dinner served.

One of my favorite rabbinic stories centers on the great teacher,

Yochanan ben Zakkai’s. Yochanan ben Zakkai escaped from the Roman occupied Jerusalem to establish a new center for learning in the northern city of Yavneh.

I was reminded of this tale when I came across a piece written by

Rabbi Toba Spitzer in which she captures the essence of the story.

It goes like this:

Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai was walking with his student – Rabbi Joshua – near Jerusalem after the destruction of the Temple. Rabbi Joshua looked at the Temple ruins and said: “Alas for us! The place which atoned for the sins of the people Israel through the ritual of animal sacrifice lies in ruins!”

Then Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai spoke to him these words of comfort: “Be not grieved, my son. There is another way of gaining atonement even though the Temple is destroyed. We must now gain atonement through gemilut hasadim, acts of lovingkindness, as it is written [in the Book of Hosea]: For I desire hesed, not sacrifice (Avot d’Rabbi Natan 11a)

In this pivotal moment, Rabbi Yochanan said:

“We must now gain atonement through gemilut hasadim, acts of lovingkindness.”

Hasadim, is the plural form of the Hebrew word hesed.

Hesed can be translated several ways

but none of the English equivalents do it justice.

Hesed is Love. Loyalty.

Or lovingkindness, according to The King James Bible.

As Rabbi Toba Spitzer says, hesed isn’t an

“emotional state but a description of a certain kind of relational action.”

It’s working with people from different socio-economic backgrounds,

demanding more equitable schools, demanding justice.

It’s listening to the tapestry of voices and stories

from amidst the prison’s walls.

Hesed happens every day within and beyond the walls of our Temple.

It is a practice, like Rabbi Yochanan so rightly said,

that can bring us closer to each other and to God.

Hesed is the step we take amidst the world’s brokenness.

Although we are finite vessels, both fragile and strong,

may we keep building,

for Emma Faye Stewart and her children,

for the young man at Sanders Estes Prison studying for his GED,

and may we do so with spirit and with care.

Shabbat Shalom.